Exclusive: Watchdog probing Starmer aide’s secret lobbying of Tory ministers

openDemocracy findings on Varun Chandra’s activities at Hakluyt prompted official watchdog to launch investigation

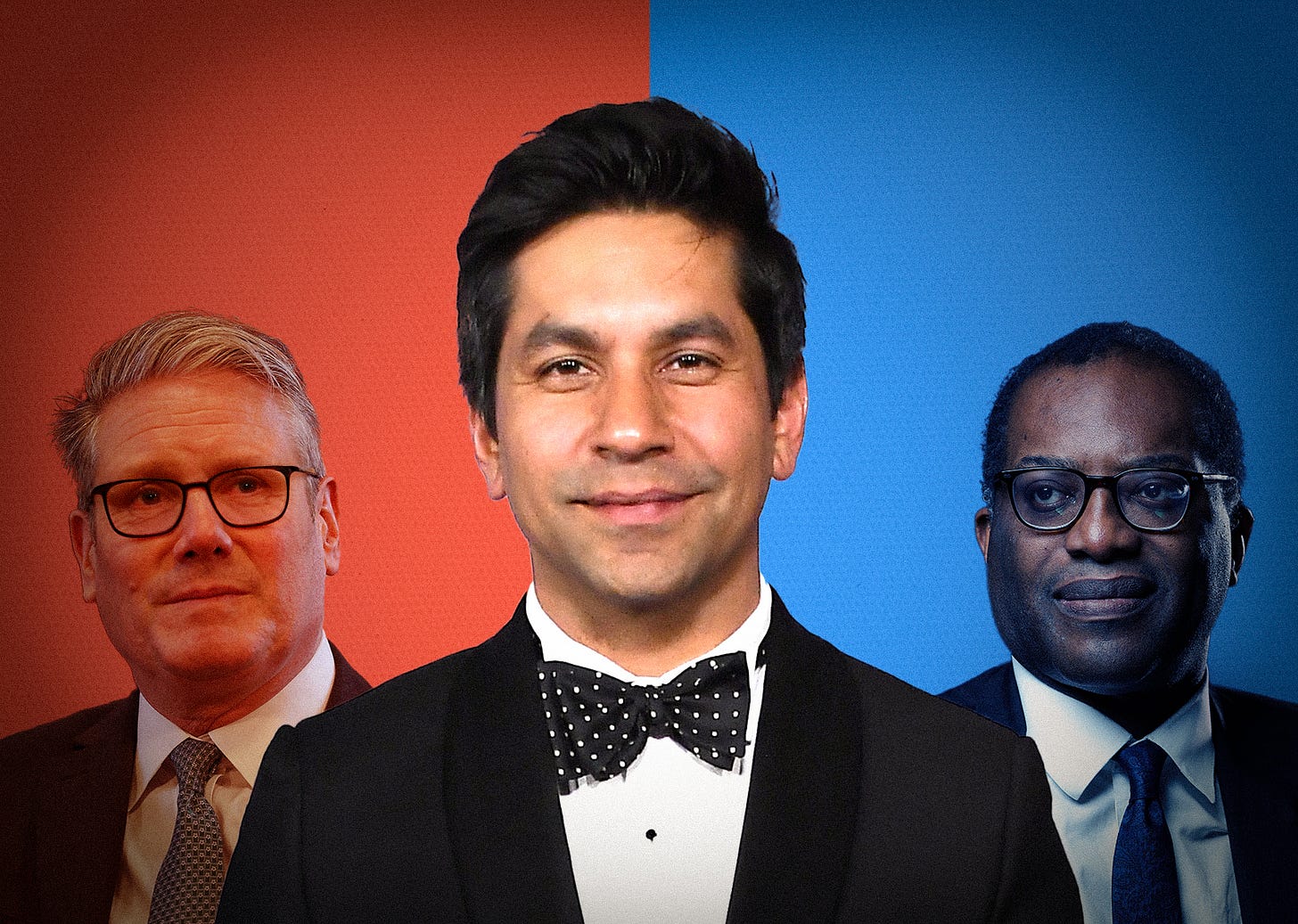

A secret meeting between finance executives and a senior Tory cabinet minister arranged by Keir Starmer’s top business aide Varun Chandra has prompted the lobbying watchdog to launch an investigation into his former firm, Hakluyt & Company.

A lengthy openDemocracy investigation has uncovered a host of meetings between Chandra and senior figures in the Conservative government. Among these was a roundtable never properly disclosed by the government, which Chandra arranged, involving then Tory cabinet minister Kwasi Kwarteng and ten leading financiers.

Hakluyt is now formally under investigation after openDemocracy shared our findings with the Office for the Registrar of Consultant Lobbyists (ORCL). Hakluyt insisted it has done nothing wrong.

As UK lobbying law only applies when lobbying is carried out on behalf of a client, this meeting with Kwarteng is believed to be the focus of the watchdog's investigation.

Today, Chandra is one of the Labour government’s most influential figures and is a central point of contact between Starmer’s Downing Street and the finance industry.

Many of the companies Chandra engaged with at Hakluyt now enjoy significant access to and influence with the Labour leadership, including asset managers Macquarie and Global Infrastructure Partners.

In his new post, Chandra had dinner with a sovereign wealth fund that attended the April 2022 roundtable meeting, which then met with the PM and chancellor Rachel Reeves the following day, as well as top civil servants, to discuss working together.

By analysing four years’ worth of government transparency records and filing more than a dozen Freedom of Information requests, openDemocracy has been able to establish the level of access and influence that Hakluyt and Chandra have had with successive administrations.

Yet widespread government transparency failings spanning several departments mean there are almost no records of the meetings that Hakluyt set up. Our investigation exposes not only the many faults baked into Westminster’s standards system but also how powerful interest groups maintain influence in Number 10 regardless of which party is in office.

Hakluyt declined to answer a number of specific questions about the events in question, but denied any wrongdoing.

“We are not a lobbying organisation – no lobbying occurred at these meetings. Any suggestion that Hakluyt has conducted consultant lobbying within the meaning of applicable legislation is entirely false,” Hakluyt said in an emailed statement.

An ORCL spokesperson told openDemocracy: “The Registrar is investigating Hakluyt in relation to potential unregistered consultant lobbying.

“A case summary will be published when the investigation is complete. The Registrar does not comment on ongoing investigations.”

‘Breakfast with Varun’

Just before 8:30am on 4 April 2022, Kwasi Kwarteng arrived at Hakluyt’s plush Mayfair office for a meeting that had been sought and arranged by Chandra, but which did not exist in the records of the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

Emails obtained by openDemocracy suggest Kwarteng may have advised Chandra to arrange the meeting through his constituency office, rather than his department.

Two months earlier, a junior staff member at Hakluyt wrote to Kwarteng’s constituency staff: “Following on from Varun and Kwasi’s recent correspondence, may I ask if there would be any preferred availability that would work for Kwasi, for breakfast with Varun and business leaders.”

Kwarteng’s assistant directed Hakluyt to the appropriate government channels, writing: “It may be best to ask his department to make arrangements for breakfast.” But the Hakluyt staffer pushed back, responding: “I think Kwasi mentioned to Varun to arrange this through yourself?”

Later in the email thread, Hakluyt asked whether Kwarteng’s private secretary, a civil servant employed by ministers to support their official work, “would also like to be included in the breakfast or best to be kept separate”. In the end, Kwarteng’s private secretary did attend. Had they not done so, there would likely be no government records at all from the meeting.

The government’s records describe the meeting simply as “breakfast” between Kwarteng’s team and Hakluyt. This means the event was likely subject to less scrutiny as it was classified as ‘hospitality’, implying it did not relate to government business.

The entry also wrongly recorded that only Kwarteng’s team and Hakluyt were present at the meeting. Additional documents obtained by openDemocracy indicate that ten finance companies attended, including private equity giants Permira and KKR and asset managers Macquarie and Global Infrastructure Partners, the latter of which is owned by BlackRock.

Kwarteng stood down at last year’s election. openDemocracy reached out to the Conservative Party and his current employer, Gunster Strategies, with a series of questions for the former minister about his dealings with Hakluyt, but did not receive a response.

A readout of the meeting reviewed by openDemocracy shows that over the course of an hour or so, the UK’s secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy offered the finance executives significant insider insights into the Tory government’s strategies, priorities and plans.

Kwarteng also took questions from the group, touching on taxation (“government will seek to keep taxes as low as possible”), industry complaints about planning processes, and some detailed, technical discussion about investment in energy structure.

Now, the ORCL is investigating whether Hakluyt should have registered as a ‘consultant lobbyist’ over the events in question. Failing to do so while carrying on the business of consultant lobbying is an offence under the UK’s only lobbying legislation, The Transparency of Lobbying, Non-Party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act 2014.

Consultant lobbying is a legal term, distinct from simply ‘lobbying’, which can refer to many activities not covered by the 2014 act. To meet the threshold of consultant lobbying, a company must not only communicate with a government minister or senior civil servant about a matter of government business, but they must do so on behalf of a third party and in return for payment. They must also be VAT registered in the UK.

Any organisation that carries on the business of consultant lobbying, whether or not they style themselves as such, is required to register with the ORCL and publish a quarterly list of the clients for whom it has lobbied. An exemption applies when a firm’s communications with a minister or official are considered “incidental” to its primary business.

ORCL can issue fines of up to £7,500 for companies and individuals who meet the definition of consultant lobbying but fail to register as such. This is widely considered to be an insufficient deterrent. Hakluyt’s annual profits were just short of £20m in 2024.

Responding to openDemocracy’s findings, Rose Whiffen, senior researcher at Transparency International, welcomed the watchdog’s decision to investigate Hakluyt.

“When a company has arranged a meeting or event with a minister on behalf of its clients and the clients are able to participate in discussions about government business, then the company should be registering as a consultant lobbyist,” said Whiffen. “Hakluyt should assist the Registrar in determining whether this was indeed a failure to register as a consultant lobbyist at the time.”

Hakluyt says it did not carry out ‘consultant lobbying’ by arranging and participating in this meeting, although a spokesperson refused to explain how, despite multiple requests from openDemocracy.

The UK has one of the least transparent lobbying regimes in the Global North, with laws that have been criticised, including by the lobbying industry itself, several parliamentary committees and other independent bodies, as overly narrow and subjective. The ORCL may find Hakluyt’s wider activities mean that it fails to meet the limited threshold for registration.

Ben Worthy, a leading academic at Birkbeck University studying government transparency, said our findings suggest the UK’s lobbying laws drastically need to be tightened to reflect the reality of lobbying.

Worthy said: “The problem here is that there are loopholes in the law itself, and in the levels of co-operation with it. This means that organisations can avoid being seen as lobbyists by using the loopholes and lack of clarity in laws themselves, and just fall into the gaps where data isn’t recorded or released.

“Any member of the public would see this as lobbying, and it illustrates once again the gap between politicians abiding with their own rules and how the public sees it, which is one of the central problems.”

The vast majority of lobbying in the UK is not registrable under the act because it is done by ‘in-house’ lobbyists, ie, individuals paid to lobby on behalf of their employer, not a third-party, or by organisations that claim that lobbying does not comprise a significant part of their business.

Small lobbying firms have pointed out that major consultancies, which carry out many activities that would otherwise be considered lobbying, do not have to register because these activities make up a relatively small part of their overall business.

‘A total clampdown on lobbying’

For the ten firms that attended the roundtable with Kwarteng, their access to power did not end when his party was voted out of government last July. openDemocracy has found that they have since met with Labour ministers and senior civil servants more than 35 times.

Over at least four occasions in the first six months after Labour took office, one of the meeting’s attendees, Temasek, a Singaporean sovereign wealth fund, met variously with Starmer, Reeves and two other senior ministers. The company also met with top civil servants in the business department and the Treasury, and even Chandra himself, who would be expected to avoid involvement with former clients — you can see a full list of Temasek’s engagement with this government here.

Another, Macquarie, an Australian asset manager that is widely referred to as a “vampire kangaroo” in UK media, has engaged with senior ministers and officials at least 14 times since the election. On one occasion, Treasury minister Lord Livermore met with “20 executives across the Macquarie Group’s C-suite and board to discuss growth, investment and regulation in the infrastructure sector”.

Such meetings are part of a wider trend of the Labour government placing great emphasis on its relationships with major investors and the financial sector. Its focus on growth driven by the private sector, and foreign direct investment in particular, suggests it sees the world of private equity as among the most important to its political agenda – further evidenced by its prominence in the industrial strategy.

Labour MP Jon Trickett has welcomed the ORCL’s decision to investigate and warned that, regardless of the outcome, “the law must be tightened to protect our democracy from abuse”.

He told openDemocracy: “These revelations are extremely concerning. It is right that the regulator now investigates whether the law has been broken. We need a total clampdown on lobbying by private companies. Profiteers should not be allowed to use their connections to influence government policy.”

“Govenrment should serve the people, not vested interests, large corporations of the wealthy,” he added.

No agenda, no minutes, no evidence

There have been at least 23 recorded engagements between Hakluyt and senior figures from government departments since 2020, five of which have taken place since Labour entered office.

openDemocracy has obtained details of 15 of these 23 engagements through Freedom of Information requests. Eight were recorded as ‘meetings’, while the rest were logged as ‘hospitality’. Whether the seven hospitality events in fact related to official government business is called into question by our findings on Kwarteng and Chandra’s breakfast.

The government is required to keep records from any meetings relating to official business. Yet in 11 of the 15 cases, it said it held “no agenda, briefing notes, minutes, readouts or other materials” – despite these being top-level meetings with some of the most influential people in government, including the then cabinet secretary, Simon Case.

One of the few meetings between Hakluyt and government officials for which records do exist took place in October 2023, when then Conservative investment minister Lord Dominic Johnson, who is now the Tory party chair, met with Chandra.

Its official summary is less than 150 words. Accordingly, this gives little away, but states that the minister “said he was keen to do a roundtable with Hakluyt’s clients”.

Weeks later, Johnson met with businesses at a roundtable to discuss the UK-Japan investment relationship. Attendees included Japanese private equity firm Itochu, which was also present at Hakluyt’s roundtable with Kwarteng, and Mitsubishi Corporation, a Japanese conglomerate that is one of the world’s largest companies.

It is not known whether this roundtable was organised by Hakluyt, and neither the company nor the government would answer openDemocracy’s questions on this. Hakluyt also refused to say whether it counts Itochu or Mitsubishi among its clients, but senior executives at Mitsubishi have had a seat on Hakluyt’s international advisory board for most of the time Hakluyt has existed.

openDemocracy shared our findings with No 10 and the Cabinet Office and asked if they would look into this pattern of non-existent and partial record-keeping, much of which took place before Labour took office.

A government spokesperson declined to answer any specific questions, instead issuing a brief statement: “Representatives regularly meet and engage with businesses and business leaders. The Cabinet Office also has a thorough process on declarations of interest for special advisers to ensure any conflicts of interest are properly managed and mitigated.”

Hakluyt’s shifting priorities

Hakluyt, which is often referred to as a ‘retirement home for spies’, was founded as a corporate intelligence firm by former MI6 operatives in 1995. Early media reports of its work centred around the intelligence it gathered for its oil giant clients, including by hiring a spy who posed as a left-wing filmmaker to infiltrate Greenpeace.

Hakluyt maintains some links to its ‘spooky’ origins. It employs the former head of the UK intelligence agency, Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), and has recently hired directly from the CIA in the US.

But its staff are now primarily former high-ranking civil servants, special advisers to government, management consultants and wonks. Similarly, Hakluyt’s work is also understood to have shifted away from its intelligence roots and towards high-level corporate strategy in recent years.

In 2019 the company was named in court documents as having worked for Monsanto to “take the temperature on current regulatory attitudes for glyphosate” within Donald Trump’s administration. Glyphosate is a component of a widely used Monsanto herbicide product, Roundup. That case, brought by cancer victim Dewayne “Lee” Johnson, resulted in a unanimous jury verdict handed down in August ordering Monsanto to pay $289m in damages, though this was later reduced to $78m.

More recently, the firm built strong ties with Labour in the run-up to the UK general election, offering hospitality to MPs Darren Jones and Peter Kyle, now the Treasury minister and tech secretary, respectively, and introduced the latter to major US tech companies and investors. It cannot be known if these firms are Hakluyt clients.

Chandra – who helped Tony Blair set up his first advisory firm after leaving frontline politics – also privately developed ties to Labour’s leadership during this time, with many Hakluyt colleagues expecting him to “move into politics”, according to a report by Harvard Business School, based on interviews with current and former members of staff.

Sources with knowledge of Hakluyt’s activities, who’ve spoken to openDemocracy on condition of anonymity, say the shift away from intelligence work has led the firm to stray into corporate lobbying. Hakluyt has repeatedly denied this, including to the government’s ‘revolving door’ watchdog, the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments (ACOBA).

ACOBA, which assesses the risks of conflicts of interest when senior politicians, advisers or civil servants leave government, has written to Hakluyt twice in recent years about former Downing Street special advisers taking up roles with the firm. On both occasions, Hakluyt “provided confirmation that it does not lobby”.

In March this year, ACOBA noted that “as Hakluyt’s clients are not known, it is uncertain whether the applicant has had any official dealings with them, or if any have bid for contracts from UK government departments or received public funds”.

Excellent work. In a healthy democracy, this article would be on the front pages of a major newspaper, or leading the nightly news. Oh well. Keep up the good work, Ethan and team and OD.

Dismantle this rigged system!